TL;DR: A simple DNS cutover for our CloudFront migration failed due to a critical limitation: the “Alternate Domain Name” conflict, which prevents a zero-downtime switch between distributions. We engineered a workaround using a Traefik-based proxy to rewrite requests, combined with Route 53 weighted routing for a safe, phased migration. This post details the “why” and “how” of this zero-downtime strategy.

How do we got here

A few weeks ago, a friend asked for my help with a puzzling CloudFront migration. He was moving a critical, high-traffic CloudFront distribution to a new AWS account and belived the cutover was complete. To his surprise, however, when checking the monitoring dashboards, he discovered that the old CloudFront distribution wasn’t draining—it was still actively serving a significant amount of user traffic.

A simple DNS CNAME flip

When I asked my friend about his migration strategy, he showed me the exact DNS change he made. He wasn’t just repoiting a record; he was evolving his setup by introducing an intermediate CNAMe for better abstraction.

The logic seemed sound. He planned to move from a direct CNAME to a more manageable, chained CNAME setup.

Here is the exact change I replicated in my own environment.

-

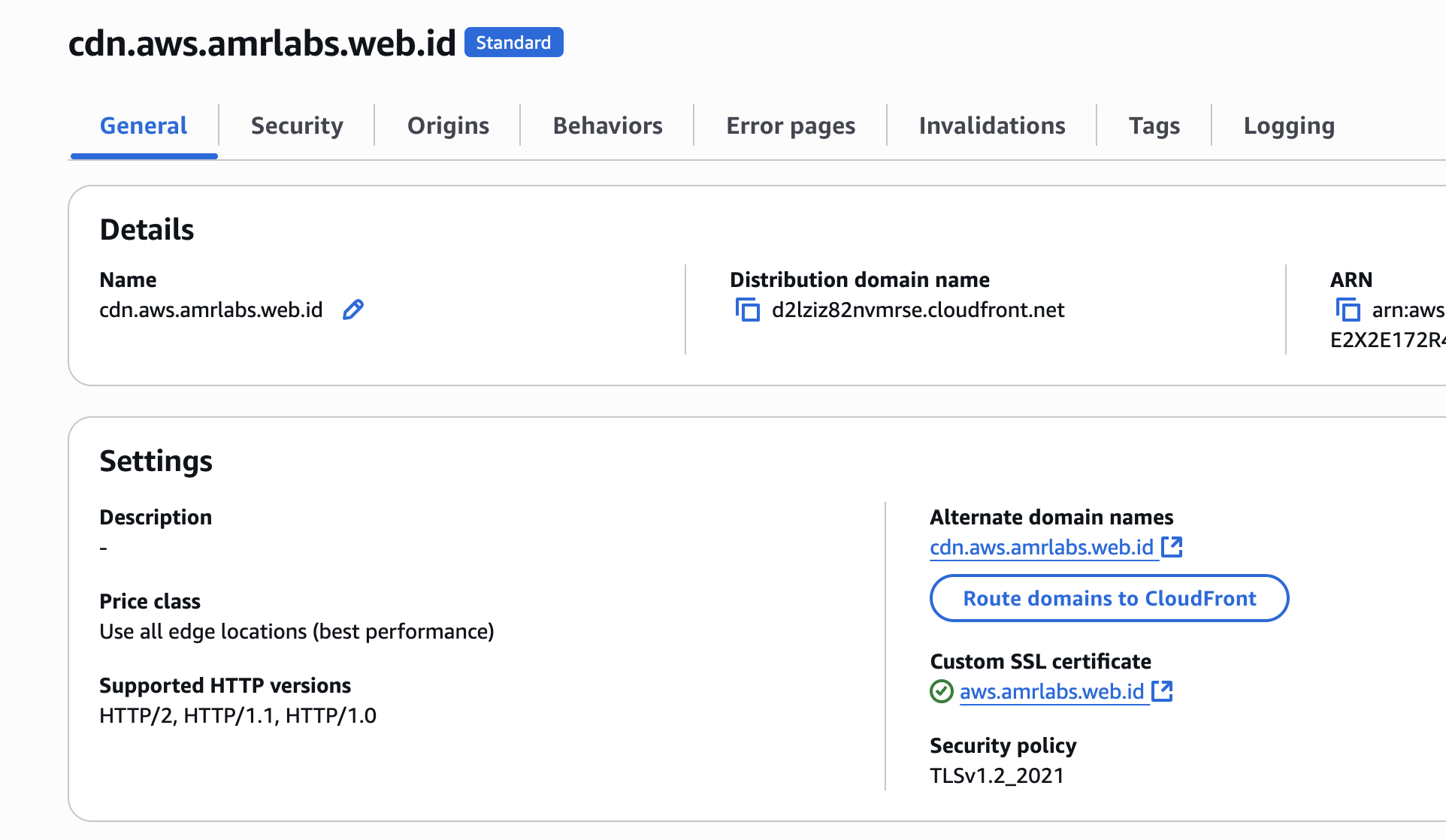

Old CloudFront distribution

- Alternate domain names:

cdn.aws.amrlabs.web.id - Domain:

d2lziz82nvmrse.cloudfront.net

Old CloudFront distribution general config

Old CloudFront distribution general config - Alternate domain names:

-

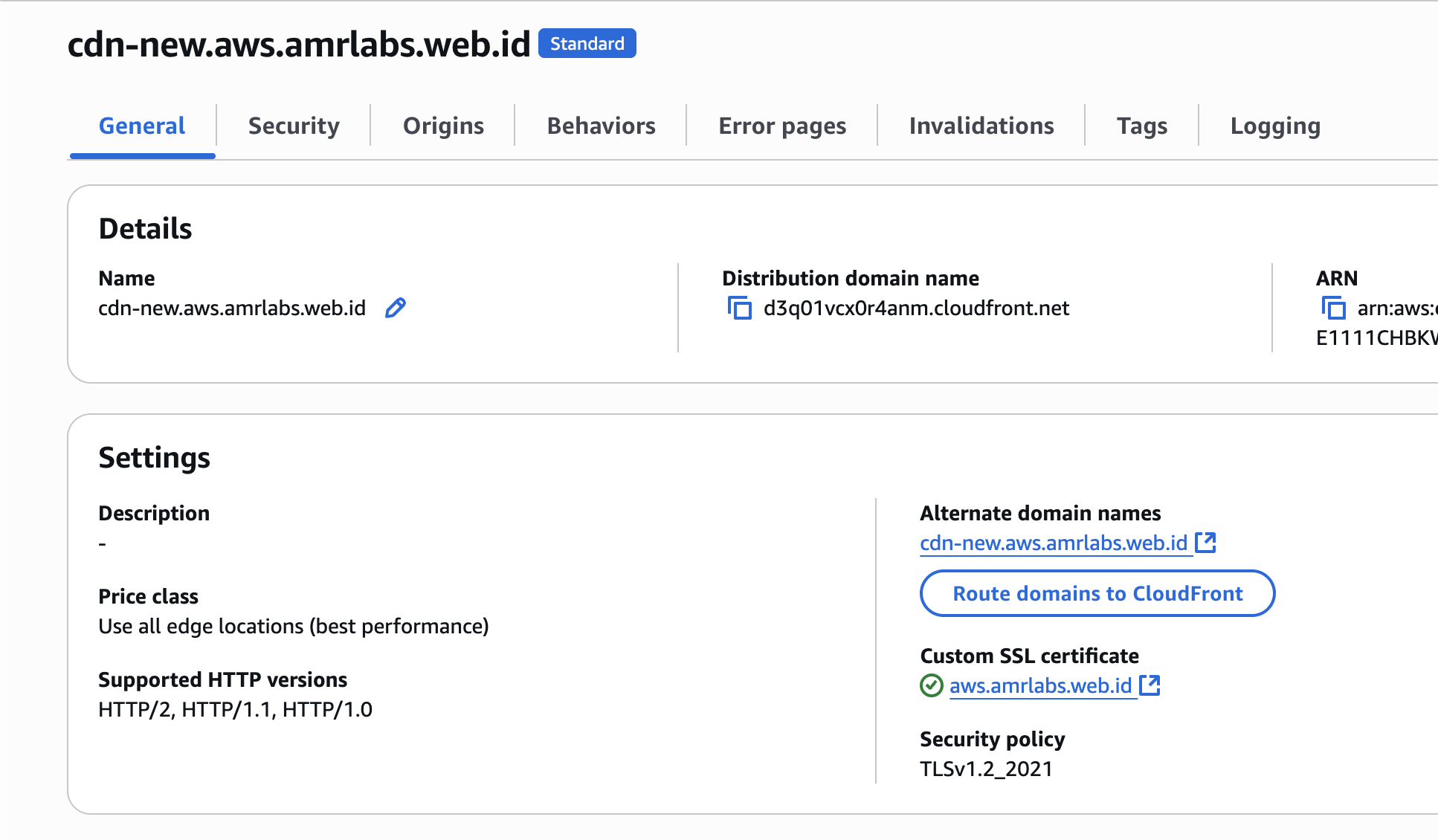

New CloudFront distribution

- Alternate domain names:

cdn-new.aws.amrlabs.web.id - Domain:

d3q01vcx0r4anm.cloudfront.net

New CloudFront distribution general config

New CloudFront distribution general config - Alternate domain names:

The migration was just this DNS change.

DNS record (before the flip):

cdn.aws.amrlabs.web.id. 300 IN CNAME d2lziz82nvmrse.cloudfront.net.

DNS record (after the flip):

cdn.aws.amrlabs.web.id. 300 IN CNAME cdn-new.aws.amrlabs.web.id.

cdn-new.aws.amrlabs.web.id. 300 IN CNAME d3q01vcx0r4anm.cloudfront.net.

The new setup introduced a layer of indirection, with the main record pointing to a new CNAME, which in turn pointed to the new distribution.

At first glance, this looks like a clean upgrade. However, this seemingly logical change was the trigger for the entire issue.

The phantom traffic he was seeing wasn’t just a simple case of DNS caching. The root cause was more subtle and was hiding in plain sight within the old CloudFront configuration: the Alternate Domain Name (cdn.aws.amrlabs.web.id) was still attached to the old distribution.

Why DNS was not enough

To get to the bottom of this, I needed to isolate the variables and see exactly how CloudFront was rouiting the requests. I set up a simple test: I put an S3 bucket behind each CloudFront distribution and uploaded a unique ruok file to each one.

The ruok file for the old CloudFront distribution:

ok-old-cdnThe ruok file for the new CloudFront distribution:

ok-new-cdnWith the test in place, I queried both the main domain and the new intermediate CNAME. The results were revealing.

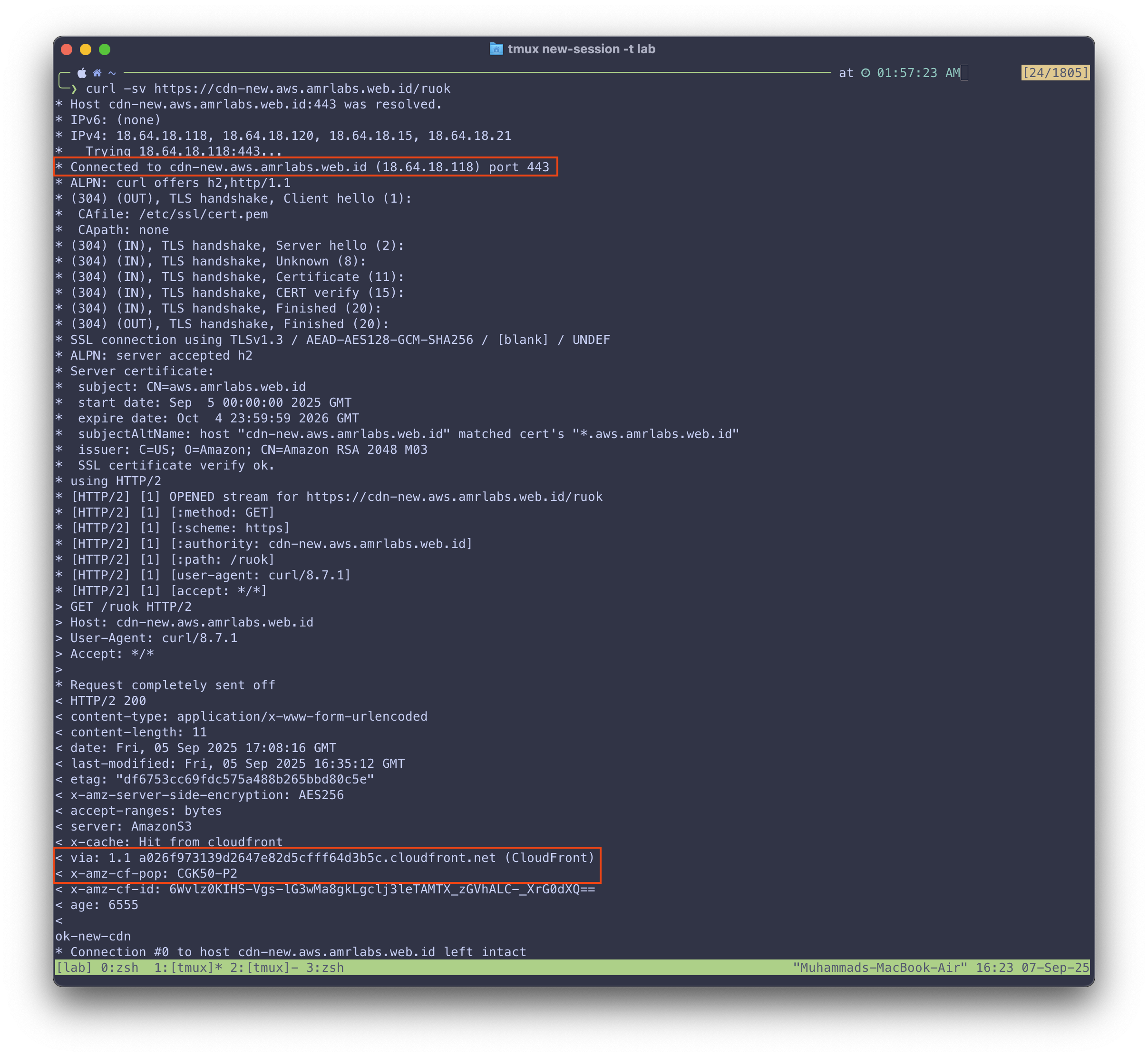

First, curling the new, direct CNAME worked as expected, returning the new file.

$ curl -s https://cdn-new.aws.amrlabs.web.id/ruok

ok-new-cdn

The detailed curl request:

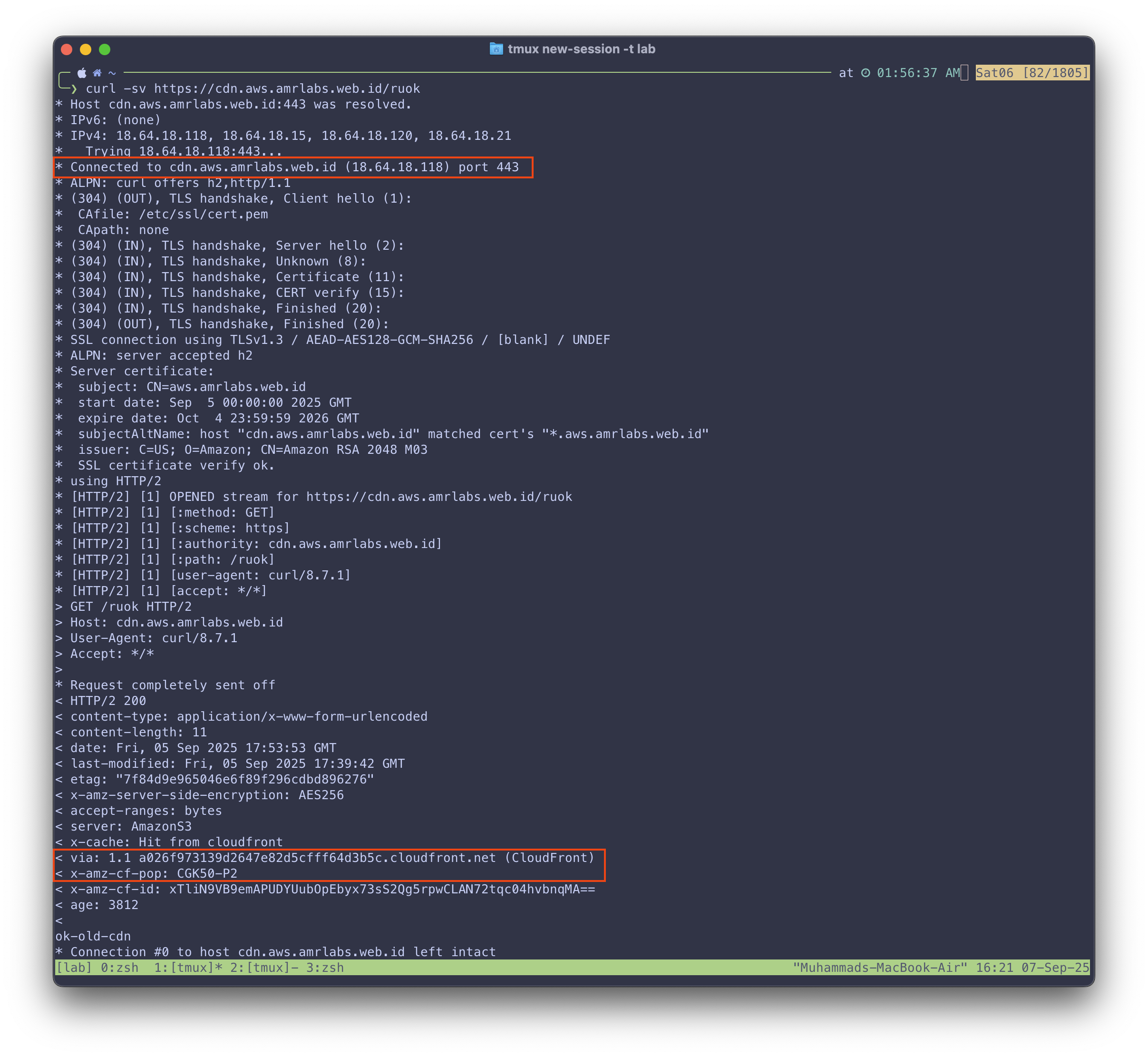

But curling the public-facing domain, which was CNAME’d to cdn-new.aws.amrlabs.web.id, gave a completely different result:

$ curl -s https://cdn.aws.amrlabs.web.id/ruok

ok-old-cdn

The detailed curl request:

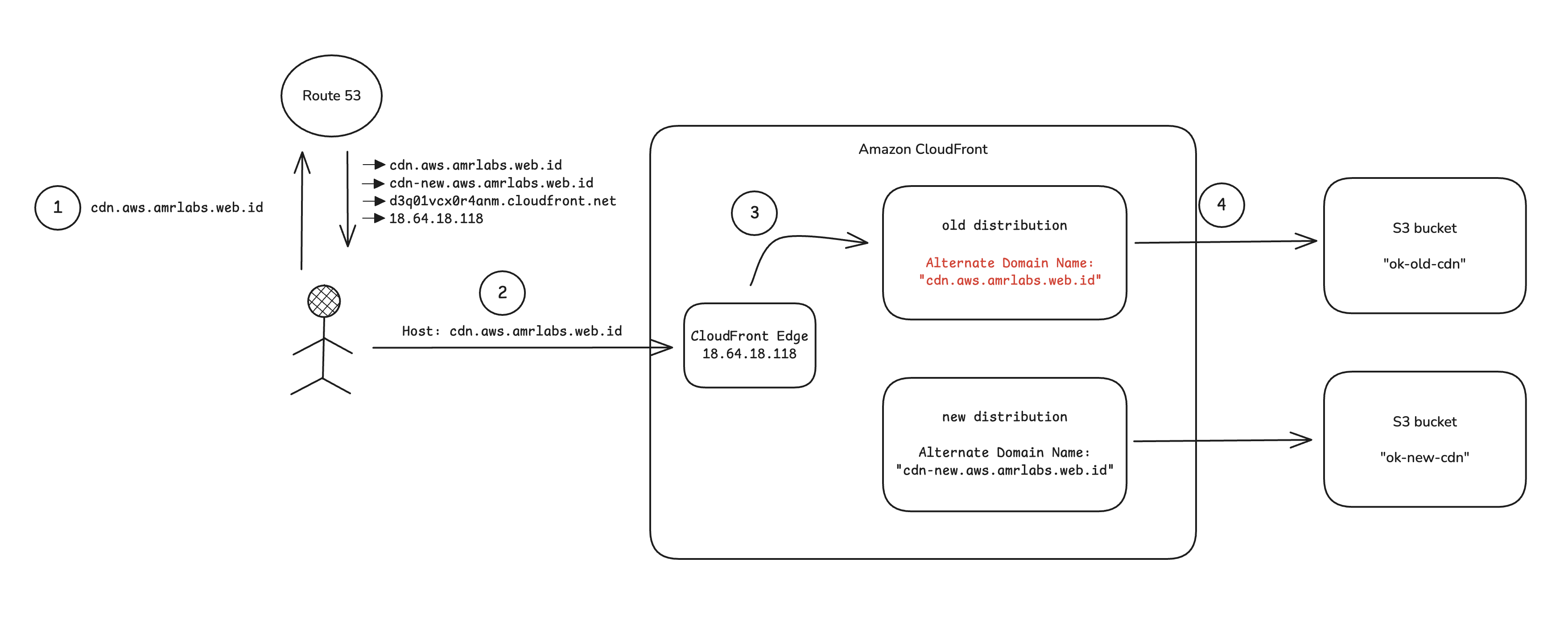

This was the smoking gun. The detailed curl -v output showed that both requests were even being served by the exact same CloudFront edge IP (18.64.18.118)!

This proved the problem had nothing to do with DNS caching or propagation. The issue was happening inside CloudFront.

Here’s what was happening:

Here’s what was happening:

- The browser sends a request to

https://cdn.aws.amrlabs.web.id/ruok. - The request arrives at a CloudFront edge server. Critically, the

Hostheader in the request is stillcdn.aws.amrlabs.web.id. - CloudFront sees this

Hostheader, finds that the old distribution still hascdn.aws.amrlabs.web.idlisted as an Alternate Domain Name, and - Serves the request from the old origin—completely ignoring the DNS CNAME record.

The DNS change was being overriden by a leftover CDN configuration.

The Fix: A zero-downtime strategy for the CloudFront catch-22

Our investigation revealed that a simple DNS change was doomed to fail. However, the real challenge wasn’t the DNS itself, but a fundamental limitation in how CloudFront handles its “Alternate Domain Names”.

The zero-downtime catch-22

Here’s the trap we faced:

- To serve traffic from the new CloudFront distribution, we needed to add

cdn.aws.amrlabs.web.idas its Alternate Domain Names. - However, CloudFront returns an error if you try to add an Alternate Domain Names that’s already in use by another distribution.

- This meant we had to first remove (“disarm”) the Alternate Domain Names from the old distribution. But this disarming process isn’t instant; it takes time to propagate across CloudFront’s global network.

Solution: A layer 7 proxy rewrite

The solution was to introduce a smart intermediary layer that could rewrite requests on the fly. We used a fleet of EC2 instances running Traefik, a powerful Layer 7 reverse proxy, to solve the Alternate Domain Names conflict.

A Note on Infrastructure: EC2 vs. Kubernetes

We specifically chose to run Traefik directly on a fleet of dedicated EC2 instances rather than in an existing Kubernetes cluster. For this critical, latency-sensitive path, we wanted to eliminate any potential network overhead introduced by a container network interface (CNI), ensuring the leanest and most performant proxy layer possible.

Step 1: The Traefik Host header rewrite

The core of the strategy was Traefik’s ability to modify requests before forwarding them. We configured it to perform two simple but critical operations:

- It would receive all incoming requests for the

Host: cdn.aws.amrlabs.web.id - It would change the

Hostheader on each request tocdn-new.aws.amrlabs.web.idand the forward it to the new CloudFront distribution’s endpoint.

Why this works: This clever trick means the new CloudFront distribution only ever sees requests for cdn-new.aws.amrlabs.web.id. We only needed to add that domain as its Alternate Domain Names, completely avoiding the conflict with the old distribution.

The Traefik configuration (conceptual traefik.yml):

http:

routers:

cdn-router:

rule: "Host(`cdn.aws.amrlabs.web.id`)"

service: "new-cloudfront-service"

middlewares:

- "rewrite-host-header"

middlewares:

rewrite-host-header:

headers:

customRequestHeaders:

Host: "cdn-new.aws.amrlabs.web.id"

services:

new-cloudfront-service:

loadBalancer:

servers:

- url: "https://d3q01vcx0r4anm.cloudfront.net"Step 2: The safety net with Route 53 weighted routing

With the Traefik workaround in place, we still needed a way to migrate traffic safely. Route 53’s Weighted Routing Policy was the perfect tool for this. It allowed us to gradually shift traffic from the old, direct path to our new Traefik proxy layer.

The DNS setup:

- Record 1 (path to old CloudFront): Points directly to the old CloudFront distribution.

- Record 2 (path to new Traefik proxy): Points to the Application Load Balancer (ALB) in front of our Traefik EC2 fleet.

This setup gave us precise control over the traffic flow and an immediate rollback path if anything went wrong.

The complete zero-downtime migration plan

With these pieces, our migration became a safe, measurable, and reversible operation executed during a low-traffic window for our Indonesian user base.

The plan was broken into two main phases: first, migrating safely to the proxy layer, and second, bypassing the proxy to establish a direct connection.

Phase 1: Migrating to the proxy layer

- We deployed the highly-available Traefik proxy fleet on EC2.

- We set up the Route 53 weighted records, with one record pointing to the old CloudFront distribution and the second record pointing to the Traefik proxy’s load balancer. Initially, we set the weight to 100% for the old CloudFront path.

- We adjusted the weights to send 1% of live traffic to the Traefik proxy.

- We closely monitored the Traefik logs and new CloudFront metrics to ensure requests were being rewritten and served correctly.

- Seeing stability, we continued to shift traffic in increments (10%, 50%, 90%) by adjusting the Route 53 weights until 100% of traffic was flowing through the Traefik proxy.

- Once all traffic was off the old distribution, we safely removed the

cdn.aws.amrlabs.web.idAlternate Domain Name from it and decommissioned it.

Phase 2: Bypassing the proxy for a direct connection

At this point, the migration was successful, but all traffic was still making an extra hop through our Traefik proxy. The final phase was to remove this temporary layer.

- We edited the new CloudFront distribution and added the final Alternate Domain Name:

cdn.aws.amrlabs.web.id. This was now possible because it had been fully removed from the old distribution. - We updated our Route 53 weighted records. The two records were now:

- Record 1 (path to new proxy): Points to the Traefik proxy’s load balancer.

- Record 2 (new direct path): Points directly to the new CloudFront distribution endpoint.

- We used the weighted policy one last time to gradually shift traffic away from the Traefik proxy and onto the new direct path. We started with 1% to the direct path, monitored for stability, and continued until 100% of traffic was hitting the new CloudFront distribution directly.

- With all traffic now bypassing the proxy, we safely decommissioned the Traefik EC2 fleet and removed its corresponding DNS record, completing the migration.

The result

By shifting our strategy from a simple DNS flip to a multi-phased, proxy-driven approach, we successfully completed the migration with zero downtime. The final architecture is now simpler and more performant after the temporary Traefik proxy layer was decommissioned.

What started as a puzzling issue became a valuable learning experience. The initial plan would have failed silently, leaving a difficult-to-diagnose problem in production. The methodical investigation and the subsequent two-phase migration plan turned a high-risk cutover into a controlled and predictable success.

Key lessons learned

This experience reinforced several crucial engineering principles. Here are the most important takeaways:

- Look beyond DNS; the truth is often at layer 7

The root cause of our issue had nothing to do with DNS propagation or TTLs. The problem was only discovered by understanding a Layer 7 concept: how the HTTPHostheader was being interpreted by CloudFront’s internal routing logic. When troubleshooting, always look up and down the stack. - Monitor the old system as closely as the new

We only caught this problem because we were monitoring the metrics of the old CloudFront distribution after the supposed cutover. During any migration, the legacy system is a critical source of truth. If it’s not completely silent, your migration isn’t truly done. - An intermediary proxy layer unlocks zero-downtime migration

The Traefik proxy was the key to solving the “Alternate Domain Name Catch-22.” This pattern—introducing a smart intermediary to handle a complex transition—is a powerful tool. It can de-risk migrations where two systems can’t own the same resource simultaneously. - DNS is an instruction, not a guarantee

We instructed traffic to go to a new location, but the CloudFront’s configuration ultimately overrode that instruction. The “trust but verify” mantra is critical for infrastructure changes. End-to-end tests, even a simplecurlcommand, are non-negotiable to verify that the system is behaving exactly as you expect.